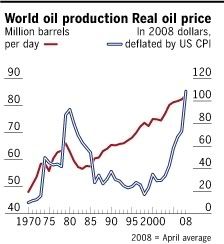

Is Peak Oil Finally Here?

But to me what is striking is how low it got between 1981 and now. My brother and I have been discussing this for years now, and our assumption was that we'd see another mean reversion.

Obviously that hasn't happened, and it has led certain commentators who would not be inclined to be doomsayers to come out and say that if this is not "peak oil," then it at the very least is a real case of supply and demand setting prices, and not "speculation." Martin Wolf (from whose column I borrowed this graph), more or less believes we should set policy as if peak oil theory were true.

We are no longer living in an age of abundant resources. It is possible that huge shifts in supply and demand will reverse this situation, as happened in the 1980s and 1990s. We can certainly hope for that happy outcome. But hope is not a policy.(He's so damn sensible, that Martin Wolf.) Paul Krugman takes a more strictly economic approach to analyzing the issue.

One of the things I find puzzling about the whole oil market discussion is how complicated people seem to make it. They get all wrapped up in stuff about forward markets, hedge funds, etc., and lose sight of the fundamental fact that there are only two things you can do with the world’s oil production: consume it, or store it.If the price is above the level at which the demand from end-users is equal to production, there’s an excess supply — and that supply has to be going into inventories. End of story. If oil isn’t building up in inventories, there can’t be a bubble in the spot price.

Again, this seems really plausible. If you think of other bubbles, like the current housing bubble, or the telecom bubble in the late 90s, or the apartment bubble of the 80s, after the crashes you were left with huge inventories. That's because speculators were building inventory with the intent of selling high later. So massive numbers of apartments (and thousands of failed S&Ls), massive quantities of fiber optic cable (and Global Crossing, WorldCom, etc.), and now huge housing inventories (and the current MBS-driven liquidity crisis). But Krugman is saying oil is different--no one is hoarding it (except for the U.S. government, and they in quantities too small to count for much).

I am going to suggest, however, that there is hoarding going on. Maybe. Krugman makes a mistake in his analysis in suggesting that you can only store oil that's been produced. On the contrary, you can store oil that hasn't been produced. That's why proven reserves are assets. Now the important thing to remember here is that most oil in the world is controlled by national oil companies--companies like Aramco, Pemex, PDVSPA, Pertamina, etc.--or by companies that if not owned by the government, are closely tied to national governments, like Lukoil.

Now if a reserve is controlled by a big, publicly-traded oil company like Exxon, BP, or Total, they have every incentive to produce as much as they possibly can right now. They have a great incentive to turn those reserves into cash while the price of oil is its highest, rather than leave them in the ground. If shareholders thought Exxon was holding back, they would flip out--and probably sue.

But a national oil company has all kinds of reasons to half-step it on production. If a nation's income depends heavily on oil, banking reserves makes sense. Because when, say, Kuwait runs out of oil, it's going to turn into a poor country overnight, a new Nauru. So policies that put off that day might be prudent.

Now Matthew Simmons (king of the peak oil guys, and certainly no crank) and many others say that, on the contrary, OPEC nations are producing at full capacity, and furthermore they are lying about their reserves. He knows more than I do--my speculation that oil producing countries are not producing as much as they could is just that (although I will offer a few supporting arguments below). But I do think he makes a mistake about their motives. He believes that the Saudis are overstating their reserves, and points to their lack of transparency as one reason for his suspicions. But why should an oil producing country be transparent? The actual size of their reserves is of strategic importance to them, so one can imagine many reasons why a country might want to understate them and keep the real number hidden. Again, their motives are quite different from a company like Shell, which is motivated to overstate its reserves for financial reasons. Saudi Arabia doesn't have to worry about its share price like Shell does. But it does have to worry about keeping its people fed and happy 25, 35, 45 years from now.

So lets look at Mexico and Venezuela. Pemex and PDVSPA are infamous for being inefficient at getting oil out of the ground. Now if Mexico and Venezuela were really interested in producing as much oil as physically possible right now, they could simply hire Exxon or Chevron or Total to do it for them. But not doing so, aside from the nationalist political benefit, keeps some oil in the ground to be retrieved in the future. This is what I'm talking about. Venezuela is using incompetence to hoard oil.

Who else is hoarding oil by not producing it? The United States. We have reserves controlled by the federal government that are not being produced, particularly ANWAR and the fields off California. And we're not the only ones.

I'm not trying to say that deliberately slow production is the sole reason for rising oil costs. Increased demand actually exists, and every barrel produced depletes some reserve somewhere by one barrel--and the cost of producing additional barrels keeps going up. But slow production and non-production has some effect on current prices.

I don't expect a correction quite like what we saw in the 80s. But I do think a combination of new technologies, new production, and economic slowdown will cause the price of oil to drop--eventually. But it will likely go up before it drops.

Labels: oil

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home